Bridging Gaps in Behavioral Health Treatment: A Narrative Summary

Introduction

The Lancet Commission on Behavioral health and Sustainable Development called for a global partnership of governmental agencies, development agencies, non-profits, and private industry to come together to transform mental health, saying “When it comes to behavioral health, all countries can be thought of as developing countries.”1 One billion people worldwide suffer from some form of behavioral health illness, costing the global economy trillions of dollars due to lost productivity and direct behavioral healthcare related costs. Investing in behavioral health treatments can not only improve morbidity and mortality, but also makes economic sense: reports indicate that every $1 spent on effective treatments for anxiety and depression returns $4 in better health and economic productivity.

Despite strong demand and growing societal awareness of the importance of behavioral health in the United States, data suggests that most Americans do not believe such services are accessible for everyone, and about half believe options are limited.a Conversely, an ideal behavioral healthcare continuum of services would include access to care, on demand, at the appropriate level, for every man, woman, and child—accessible, high quality, multimodal treatment brought to the individuals who need it. b

Behavioral Health Care Gap Example: Clinician Shortages

In the United States, the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates that 51.5 million adults aged 18 and older live with a behavioral health illness—20.6% or one in five of all adults2. However, behavioral health care has been chronically underfunded, unaffordable, and inaccessible in the U.S. for many individuals3. A national shortage of behavioral health providers combined with poor reimbursement and restrictive insurance coverage for behavioral health services has made it difficult for many Americans to access care for behavioral health concerns. NIMH reports that in 2019, only 44.8% of American adults with behavioral health issues received adequate treatment4.

The Substance Abuse and Behavioral Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reports that the U.S. needs approximately 4.5 million additional behavioral health professionals to provide care for the current population to address behavioral health and substance abuse issues; with a current estimated behavioral health workforce at about 700,000 professionals, that is a staggering 87% workforce deficit.8, 9

The growing shortage of board-certified psychiatrists is further emblematic of a greater problem. Of the roughly 30,000 psychiatrists in the U.S., nearly 60% are age 55 or older, placing psychiatrists as third of 23 medical specialties, among the list of the oldest physicians (only pulmonology and oncology have higher percentages over age 55.)9 The number of new psychiatrists entering practice has not kept pace with population growth and demand, let alone with the expected the number of psychiatrists likely to retire. Moreover, it is estimated that currently 60% of all counties in the U.S. lack even a single psychiatrist.10 Combined with the fact that psychiatrists are the least likely amongst office-based specialists to accept insurance, access to these specialists has become exceedingly difficult for the average American and not surprisingly primary care physicians are assuming an ever-growing responsibility for psychotropic prescribing in the U.S.11

Impact of COVID-19 on Behavioral Health Treatment

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to precipitate widespread fear, bereavement, isolation, and economic disruption, magnifying the paucity of existing behavioral health resources and straining an already limited behavioral health infrastructure. However, limitations on office-based visits in the service of social distancing has brought the liberalization of reimbursement for non-face-to-face, remote services catalyzing the broad adoption of “virtual visits”5 and digital health tools as stand-alone treatment or extensions of providers—through the pandemic, telepsychiatry is increasingly the “norm” having shifted treatment from medical offices and treatment facilities to the home.13, 14

Behavioral health has been poised for rapid adaption of telemedicine with the routine psychiatric assessment being less dependent on physical examinations or other physical diagnostic assessments. Data collected from November 2020 through February 2021 suggests that 33% of all behavioral health appointments were conducted virtually6 followed by primary care (17%), pediatrics (9%), cardiology (7%), and OB/GYN (4%). Another national survey suggests most behavioral health organizations were using telehealth for at least half of all consumer visits, though utilization varied greatly by region.15, 16

Telehealth has therefore demonstrated a potential path towards expanding access to behavioral health services especially with the gravitation of consumers and providers towards more mobile and tech-enabled care. While the degree to which this telehealth adoption will endure post-pandemic, many are hopeful that financial incentives will remain to consolidate and expand these types of behavioral health services. For example, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has indicated that many of the telehealth expansions allowed during COVID will be made permanent. There were 144 telehealth services temporarily covered by Medicare in 2020 during the height of the emergency, nine of which—such as group psychotherapy and care planning services—will be covered permanently7. Similarly, at the commercial insurer and state Medicaid levels, a multitude of reimbursement changes have been implemented to make telehealth more accessible to providers and consumers.13, 14

National Forum: Expert Consensus to Addressing Gaps in Behavioral Health Treatment

As noted, the behavioral health clinician shortage is a significant gap in the health treatment system, but potential solutions do exist, including the employment of digital technologies and loosening of reimbursement regulations for telehealth. However, there remains much to be learned. Though the perspectives of healthcare providers in bridging treatment gaps in behavioral are important, they are largely absent from the literature. In the PsychU National Forum, “Bridging the Care Continuum,” a panel of nine experts met on October 13-14, 2020, to address the issue. The event was chaired by Brandon Kitay, M.D., Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Emory University School of Medicine and Director of Behavioral Health Integration at Emory Healthcare. The seven key topic areas discussed reflected thematic responses from a survey of PsychU Members reflecting a cohort of healthcare professionals across the United States.

- Bridging the Care Continuum.

- Views of Behavioral health Care and Collaborative Care.

- Barriers to Bridging the Gap.

- Payers and the Behavioral health Care Continuum.

- Treatment Approaches to Bridging the Gap.

- Digital Health Technologies and Mental Health.

- Discussion on Educational Resources.

PsychU Survey on Bridging the Care Continuum

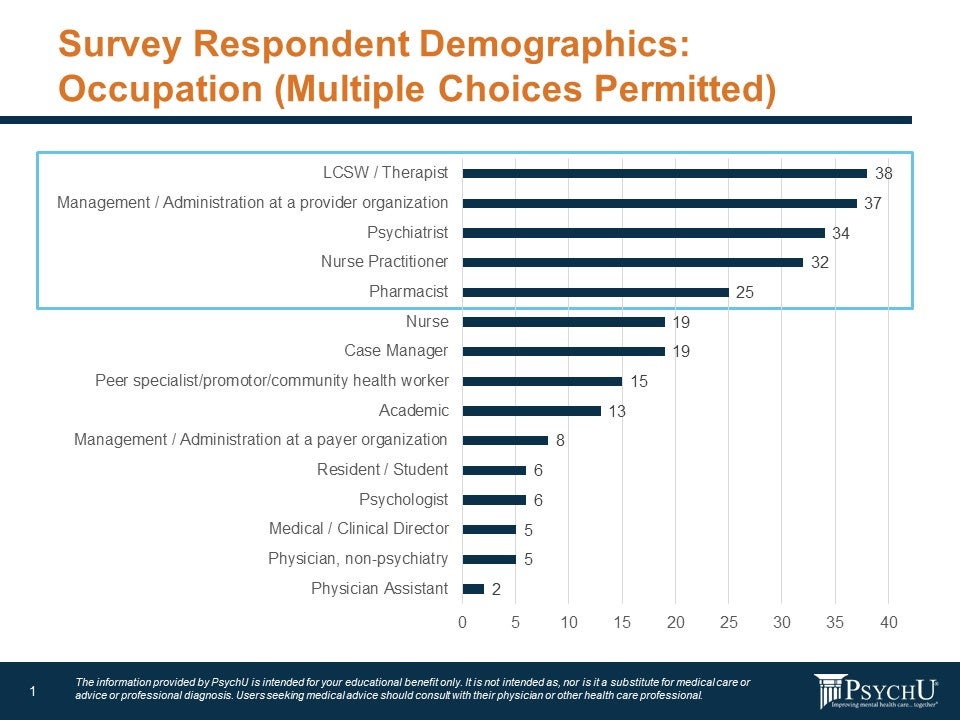

A central piece of the discussion were the results of the digital survey conducted between September 7, 2020, and September 29, 2020, of 220 healthcare professionals sampled from PsychU.org members. The survey was conducted online as advertised through targeted PsychU e-mail blasts and social media posts and distributed directly to healthcare professionals by Otsuka medical science liaisons (PsychU is supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. (OPDC), Otsuka American Pharmaceutical, Inc. (OAPI), and Lundbeck, LLC.). The top five professionals who provided responses were therapists, managers of a provider organizations, psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists (Figure 1).

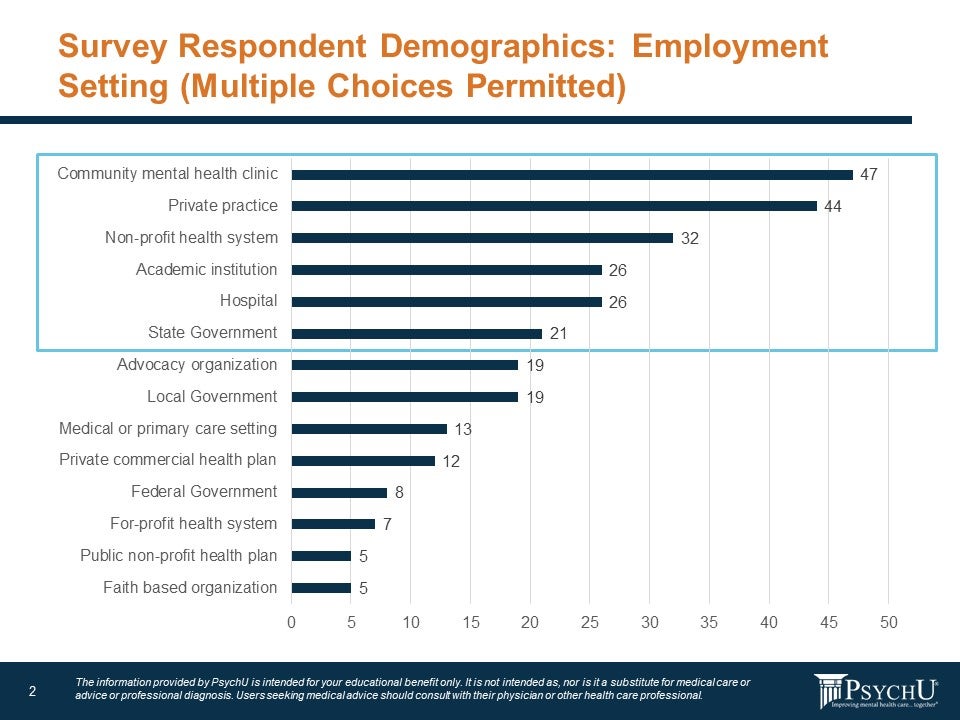

Respondents were also queried about healthcare setting, with the top five responses being: community behavioral health clinic, private practice, non-profit health system, academic institution, and hospital (Figure 2).

Figure: Survey Demographics

Figure: Employment Setting

Expert Consensus Topic 1: Bridging the Care Continuum

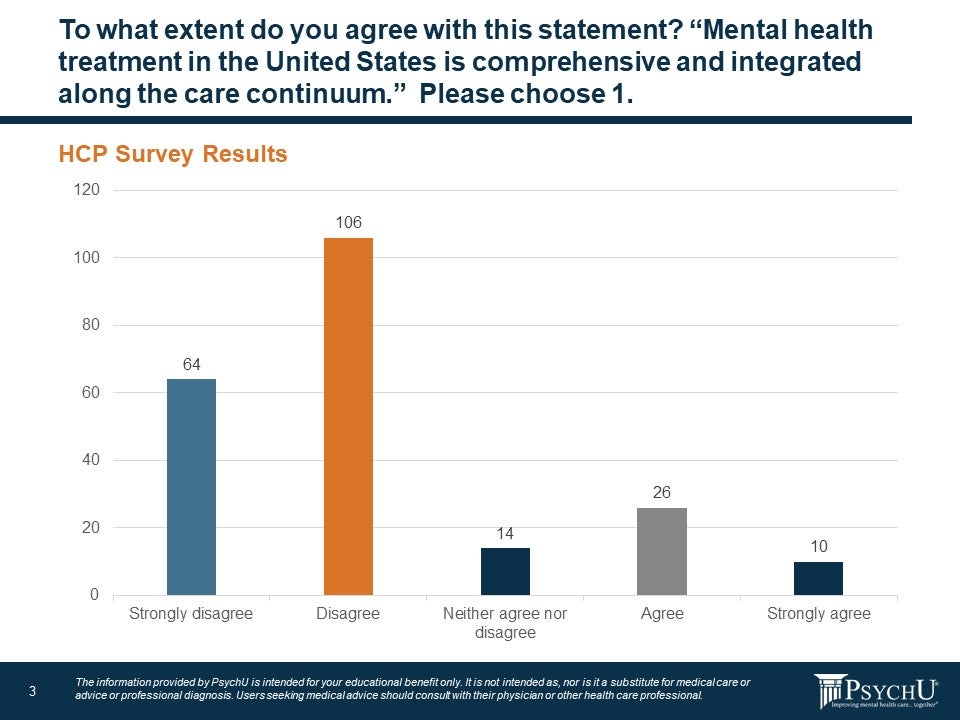

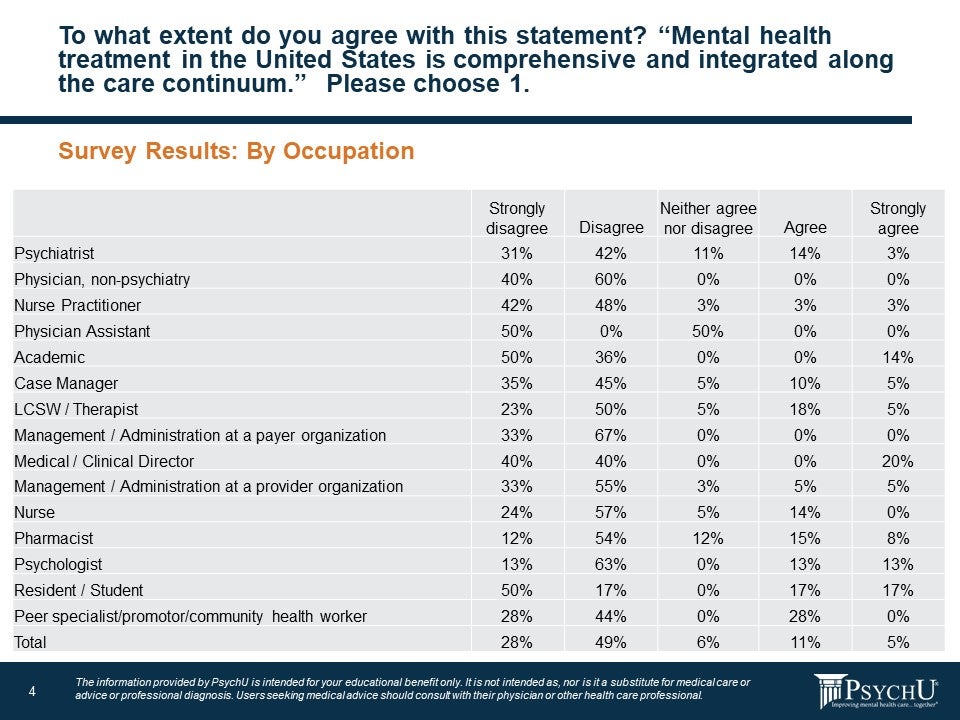

Currently, one of the most significant issues is the disconnection of behavioral health from the rest of health care. According to the survey, just 16% professionals surveyed “agree” or “strongly agree” that behavioral health is comprehensive and integrated while 77% “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with that statement. About 6% of respondents answered that they were unsure and neither disagreed nor agreed with the statement.

Results tended to vary depending on the occupation of the respondents. Clinicians in the field, such as psychiatrists, physicians other than psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants were largely pessimistic about the efforts thus far to integrate behavioral health into medicine in general. About 73% of psychiatrists and 90% of nurse practitioners responded they felt field was not integrated. However, therapists (23%), medical directors (20%), pharmacists (23%), psychologists (26%), and peer specialists (28%) were more likely to agree or strongly agree that behavioral health is indeed integrated into healthcare generally.

Figure: To what extent do you agree with the statement? “Behavioral health treatment in the United States in comprehensive and integrated along the care continuum” Please choose 1.

Figure 4: To what extent to do you agree with this statement? “Mental health treatment in the United States is comprehensive and integrated along the care continuum.” Please choose 1.

In order to generate novel themes for discussion, we further surveyed respondents via a free-response inquiry to define, in their own words, the meaning of the phrase “Bridging the Care Continuum,” as it pertains to behavioral health. Responses were categorized with these top three themes emerging:

- Need for coordination of people and systems.

- Integration of physical and behavioral health.

- Pessimism.

Coordination of Systems and Programs

One of the top three themes to emerge was a clear need for coordination between programs (e.g. levels of care) and health systems addressing behavioral health issues. Qualitative responses included:

- “Connecting across organizations, systems and providers.”

- “Services flow easily from provider to provider or program to program.”

- “Inpatient to outpatient seamless”

- “Inmate behavioral health during incarceration.”

- “Linkage.”

- “Coordination.”

- “Integration”

Integration of physical and behavioral health

Survey respondents indicated they generally feel there should be better integration of “emotional well-being,” along with “physical well-being,” in healthcare settings. Qualitative responses included:

- “Ensuring that medical and psych work together.”

- “Coordination with primary care.”

- “Ensuring that everyone gets the care they need.

Pessimism

Another theme to emerge is that behavioral health providers are not optimist about bridging the gap between physical health and behavioral health. Qualitative responses included:

- “Lofty goal.”

- “Wishful thinking.”

- “Disgraceful mess.”

- “Means nothing.”

- “What is the continuum anyway?”

The need to develop continuing education (CE) programs was also an emergent theme, as a mechanism for enhancing awareness and competency of basic behavioral health issues amongst potential coordinating partners (e.g. primary care).

Some suggestions from Forum participants to overcoming barriers to implementing collaborative care include:

- Providing greater access to educational content for primary care providers (PCPs) on the management of the most common behavioral health illness seen in primary care and guidelines for referring to specialty behavioral health follow up

- Establish common measurements to allow PCPs, nurses, and behavioral health consultants/paraprofessionals to meaningfully track patient progress through primary care- based treatment over time.

- Establish best practices for documentation to ensure consultants and referrals have necessary information in an efficient and meaningful format.

- Continue to build upon pandemic driven the enhancements in communication with telehealth and electronic health reporting. Many of these initiatives have been discussed for years, but the pandemic accelerated implementation and demonstrated the utility of expanding telehealth resources to improving behavioral health access. It is important to keep these services in use and reimbursed going forward.

Expert Consensus Topic 2: Views of Behavioral health Care and Collaborative Care

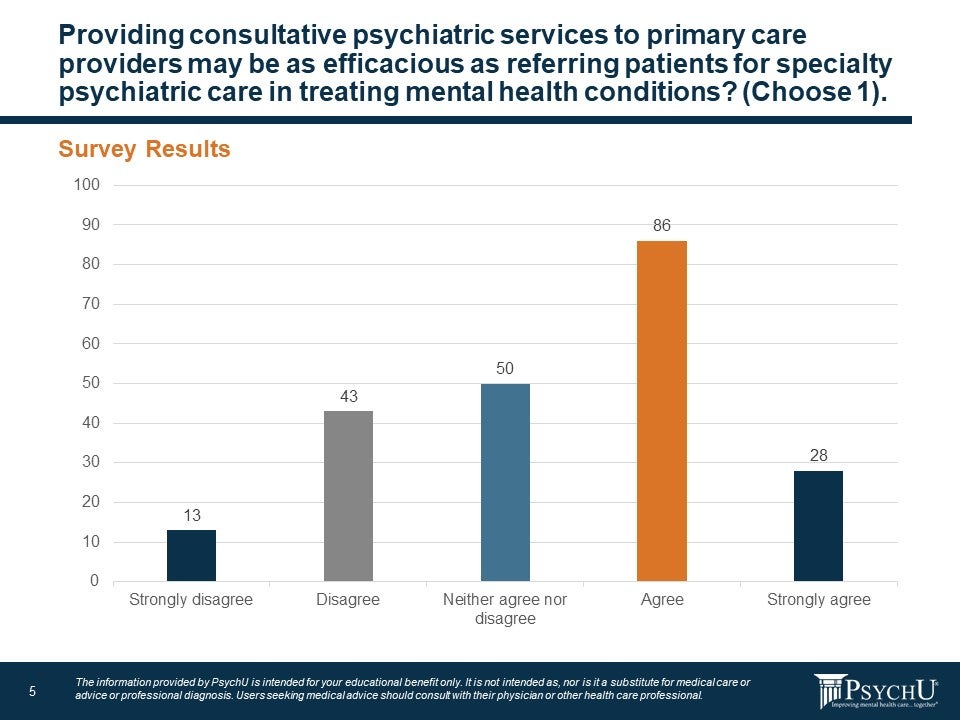

A critical issue in coordinating services between primary care and behavioral health providers is establishing mechanisms to facilitate this coordination and communication. One well-established, evidence-based approach has been to integrate behavioral health into primary care via co-location of services or implementing “Collaborative Care” models, all of which attempt to mitigate barriers to patient access by housing services in the same physical location. Mental health providers are warming to the idea that psychiatric services provided as part of a joint venture with primary care or other medical specialties can be as effective as a separate referral to specialty care congruent with a strong evidence-base supporting this assertion. More than half the survey respondents (52%) said they agree or strongly agree that combined care can be as effective. A quarter of respondents (25%) said they disagree or strongly disagree that it can be as effective while 22% were neutral on the question.

Figure 5: Consultative Psychiatric Services to Primary Care Providers

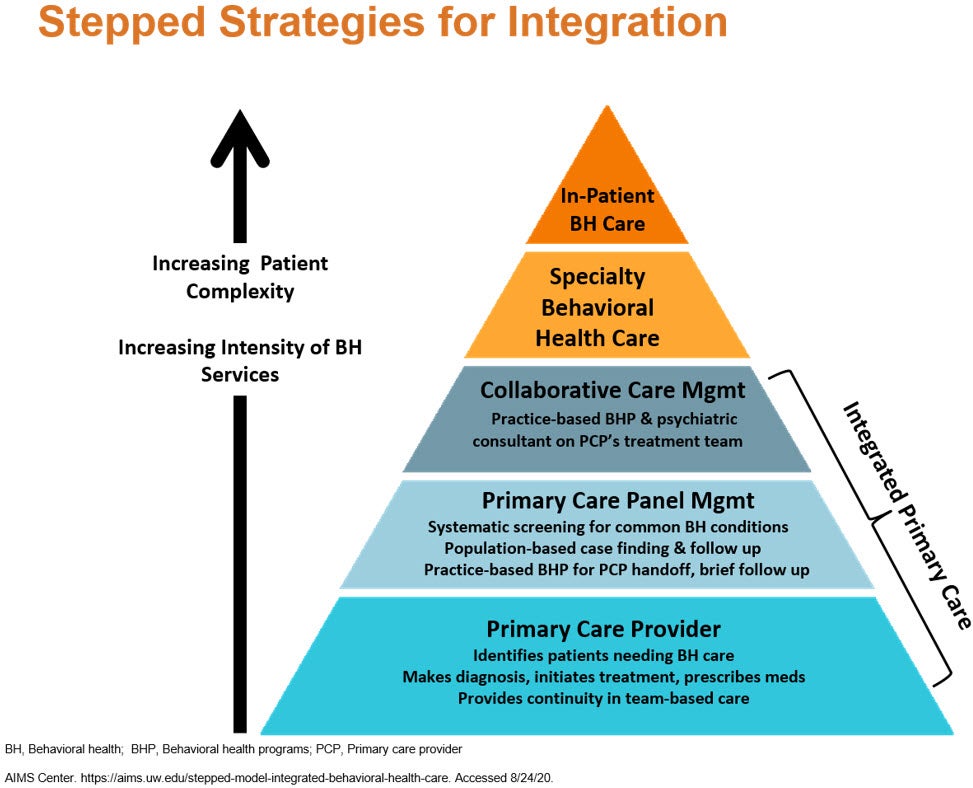

But what is integrated care exactly? Simply put, integrated health care is the systematic coordination of behavioral health care with other medical services. This means aligning behavioral health care for depression, anxiety, or addiction treatments, with primary medical care. The benefit of this approach is compounded for those with more than one health condition or comorbidity: medical and behavioral health treatment can become highly coordinated amongst a team of providers in a central location. Evidence supports that this approach is more efficacious than standard referral-based treatment approaches for both psychiatric and medical—that is, these models of care are more than just enhancing convenience for patients and their families, they are truly better forms of treatment with improved outcomes.17, 18 Moreover, integrated care is especially important for marginalized communities that often lack access to high-quality health care and for whom stigma represents a major barrier towards engagement in behavioral health treatment.

There are a many different models for integration that range from limited consultation with a behavioral health specialist either on-site or remotely fully integrated systems with both primary care and behavioral health treatment available within the same site. Many of these models with elements that relied upon telehealth were well suited to further implementation and expansion through the COVID-19 pandemic and again reflect the potential for growing reliance on telehealth to improve coordination and integration of primary care and behavioral health services.

Figure 6: Stepped Strategies for Integration

With the wealth of educational resources and implementation materials available for implementation of the Collaborative Care (CoCM), a model with its own CPT codes for reimbursement by third-party payers, Forum participants had specific suggestions to enhance adoption of this integration model including:

- Improve and streamline collaborative care reimbursement codes to motivate primary care providers (PCPs) to focus on whole person health and not just symptom management.

- Encourage behavioral health providers to build relationships with PCPs to better understand the challenges they face. This can be done through sharing a shift at a primary care clinic, shadowing a PCP, and/or cross-hiring, such as hiring a family practice nurse practitioner vs. a psychiatric nurse practitioner to bring in outside experience.

- Employ better use of care coordinators and other professionals who can act as intermediaries for patients seeking care.

Expert Consensus Topic 3: Barriers to Bridging the Gap

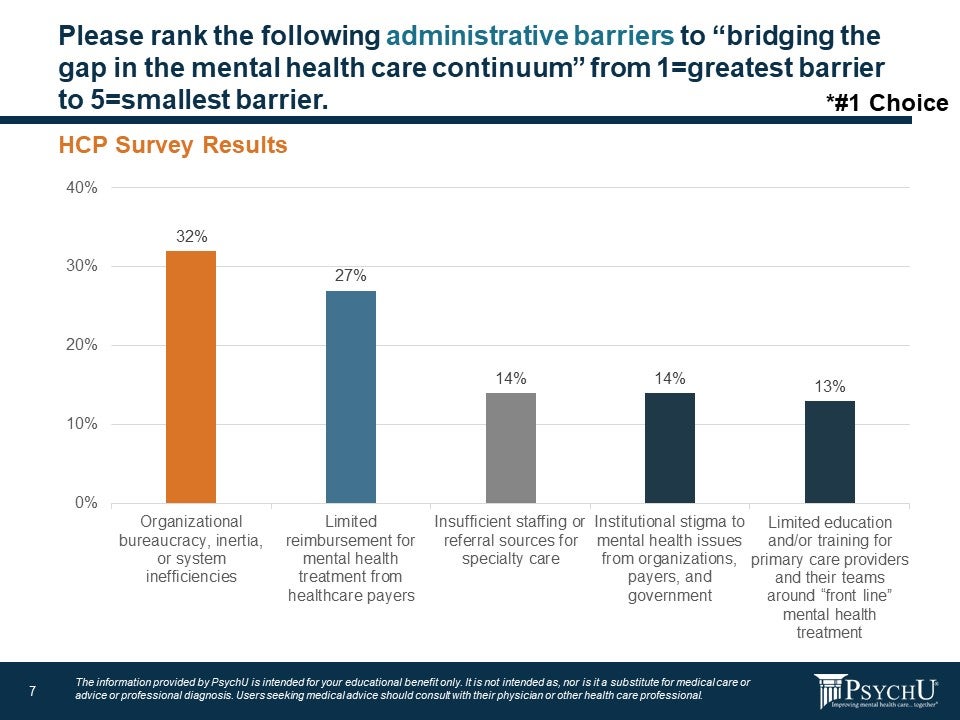

When asked about specific barriers to care, providers who responded to the survey said their top concerns were organizational bureaucracy, inertia, or system inefficiencies (32%) and limited reimbursement for behavioral health treatment from healthcare payers (27%).

According to Forum attendees, employers are increasingly recognizing the need for employee behavioral health services. The challenge historically has been shifting the tendency of large employers to simply contract for behavioral health services to fully embracing the importance of a collaborative approach. Forum participants pointed out that innovative payors are beginning to incentivize behavioral health providers to pair with primary care providers, for example, through bonuses for establishing such relationships. Once partnerships are developed, payors can further incentivize these relationships through measurement-based care outcomes and quality metrics.

Figure 7: Administrative Barriers to Bridging the Gap

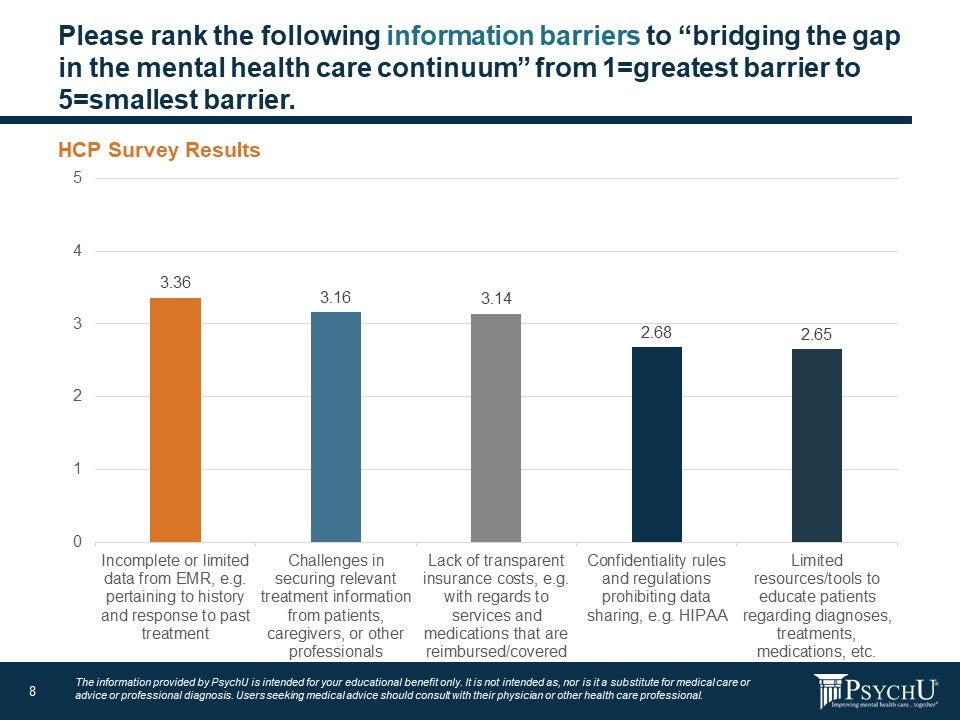

Another important issue related to collaborative or integrated care is information barriers that prevent effective communication between providers, patients, and payors. When asked what the largest information barrier was to bridging the gap in behavioral health, 53% said it was incomplete or limited data from the electronic medical record (27%) and lack of transparent insurance costs with regard to what services and medications are reimbursed/covered (26%). The lack of communication between other providers and payors leads to information gaps that are a problematic barrier to effective treatment.

Figure 8: Information Barriers to Bridging the Gap

Expert Consensus Topic 4: Payers and the Behavioral health Care Continuum

Regarding the role of insurance companies in improving behavioral health, survey respondents were asked the following open-ended question: “How do health care payors impact ‘bridging gaps in the mental healthcare continuum?” The three main themes that emerged were:

- Rife with obstacles and roadblocks.

- Need for parity.

- Not all bad?

Rife with Obstacles and Roadblocks

Survey respondents admitted they were frustrated by how third-party reimbursement can act as a barrier to behavioral health treatments. Responses included:

- “Where is behavioral health parity? Healthcare payers are a barrier to behavioral health care.”

- “Insurance often puts up roadblocks to care.”

- “Denial of services or putting steps in place can impede individualized recovery.”

- “They only do what regulation allows them to do, so let’s start at the top with federal policies.”

- “They can make or break whatever system is in place.”

Need for Parity

Though parity has been Federal law since 2008, health insurance plans still charge higher co-payments and other out-of-pocket costs for behavioral health and substance use disorders than for medical or surgical treatments.20 However, there are many nuances to how health insurance companies reimburse for behavioral health services. For example, smaller groups (usually under 100 employees) may be exempt from the federal parity laws and other states have parity laws stricter than federal statue. As such, many behavioral health providers lament that parity has not yet been achieved. Responses related to parity in response to how payors can bridge the gap include:

- “By assuring that the patient’s physical and behavioral health needs are assessed and met at every encounter.”

- “Parity in funding behavioral health services.”

- “Behavioral health (behavioral health and substance use disorder) should not be separate categories in health care insurance plans – true parity would not be separate.”

- “They can pay more for collaborative care.”

Not All Bad?

Generally, survey respondents agree that parity between behavioral health and physical health has improved over time, but many believe the system still needs some work. Qualitative responses included:

- “They are a great source in bridging the gap as long as they are active.”

- “Inconsistently: Some payers are great; others still don’t provide parity.”

- “Payers are better than 10 years ago, but much improvement is still needed.”

Forum participants agreed that parity can be difficult to achieve due to different rules depending on the state and locality in question, as well as authorization rules for in network versus out of network treatment. Suggestions from Forum participants for improving parity between behavioral health and primary care services, included:

- Consider “secret shopper” surveys to gather data about reimbursement. This type of data will be key towards identifying and reporting disparities back to the payor.

- Press for more integrated and collaborative care models to ensure parity.

- Consider lawsuits as a last resort to when parity cannot be achieved otherwise.

Expert Consensus Topic 5: Treatment Approaches to Bridging the Gap

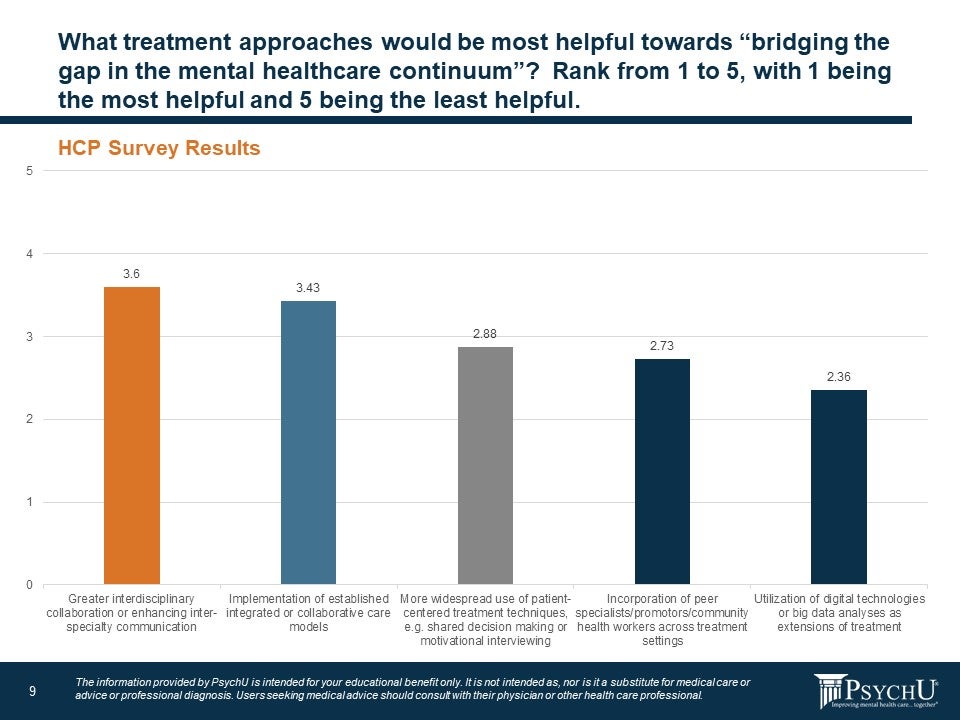

Regarding treatment approaches to help bridge the treatment gap, 56% of the survey respondents said interdisciplinary collaboration or enhancing inter-specialty communication (30%) and implementation of established integrated care or collaborate care models (26%) would help most. About a third of respondents said more widespread use of patient-centered treatment techniques, like shared decision making or motivational interviewing (16%), and incorporation of peer specialists, promotors, community health workers across treatment settings (16%) was the best approach. Only 13% of respondents reported the best way to bridge the gap would be through better use of digital technologies or big data analyses as extensions of treatment.

Figure 9: Treatment Approaches to Help Bridge the Gap

Forum participants agreed that improving communication and expanding the use of integrated care models will help transform the system and bridge the gaps in treatment. Suggestions from Forum participants included:

- Modeling best practices in successful integrated healthcare systems such as within prisons, jails, and the Veterans Administration

- Publish articles about integrated care success or how collaborative care can improve patient outcomes and reduce costs. Encourage publication of these articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Expert Consensus Topic 6: Digital Health Technologies and Mental Health

Survey respondents were asked the open-ended question, “When you hear the term ‘digital health technologies’ for behavioral health, what comes to mind?” Themes from providers who took the survey coalesced under three main topics.

- Tele-treatment.

- Optimism for digital solutions.

- Counterbalance of concerns.

To set the discussion for telemedicine, it is important to remember that in 2020, telehealth was typically available for rural patients without access to local providers. Even then, patients sometimes were required to be physically present at an approved health care facility to virtually see a designed provider at another location. The rules were relaxed during the pandemic to allow patients and providers to receive and deliver care from home to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in medical clinics. This home-based care, which has been largely popular among patients, allowed telehealth to expand.

Some behavioral health providers report that many patients have fewer no-shows when compared with in-person appointment treatment.21 Health practices have consistently reported lower no-show rates with telehealth, especially in behavioral health where telehealth removes the stigma of visiting a behavioral clinic. For example, the baseline no-show rate for psychiatry services had been 19% to 22% of appointments, while the MDLive telehealth platform reports no-show rates of 4.4% to 7.26% for its behavioral health telehealth visits.22

Throughout the pandemic, Medicare has reimbursed telemedicine visits at the same rates as in-person office visits. However, outside of the public health emergency declaration, Medicare pays a lower rate for telehealth services compared to office visits. Post-pandemic, Congress and payers must determine a long-term strategy for telehealth, weighing the popularity of its convenience with patients and the scientific evidence regarding efficacy and affordability.

Medicare normally requires patients and medical providers to interact in real time over video technology. Again, Medicare waived this requirement during the pandemic to allow for some visits to be conducted exclusively through telephone without a video component. During the emergency, CMS has been reimbursing audio-only visits at the same rate they do in-person office visits. Although there is debate among providers about whether audio-only visits provide the same level of care as video or in-person visits, telephone visits have allowed many patients to have access to health care who might not have had it otherwise.23

Historically, state medical laws required providers to be physically based in the same state as the patient receiving treatment. However, many of these laws were modified during the pandemic to facilitate behavioral health care, making more timely treatments possible and helping to equalize supply and demand imbalances.

Tele-treatment

Another issue with tele-treatments is that the industry has not yet coalesced around what exactly to call it. Here are a few qualitative answers from respondents about how they would describe tele-treatments:

- “Online healthcare.”

- “Videochat.”

- “Teledoctor.”

- “Telemedicine.”

- “Telepsych.”

- “Teletherapy.”

Optimism for Digital Solutions

The good news is that survey respondents generally feel optimistic toward digital solutions in behavioral health. Terms used to describe it are:

- “Practical.”

- “Convenient.”

- “Increased access to care.”

- “Better care.”

- “Useful.”

- “Wearables.”

- “EHR.”

- “Apps.”

- “Computers.”

Counterbalance of Concerns

While providers are optimistic about the benefits of digital solutions in behavioral health care, many expressed concerns that the technology is less personal and that more data regarding efficacy is needed. Some providers are wary of the technology solutions, worrying that the methods are too technical—both for providers and patients. Qualitative answers included:

- “Dehumanize and control.”

- “Impersonal.”

- “Too technical.”

- “Need more education.”

- “Will this be helpful?”

- “Is it a proven effective mode of therapy delivery?”

Barriers to Digital Technology Implementation

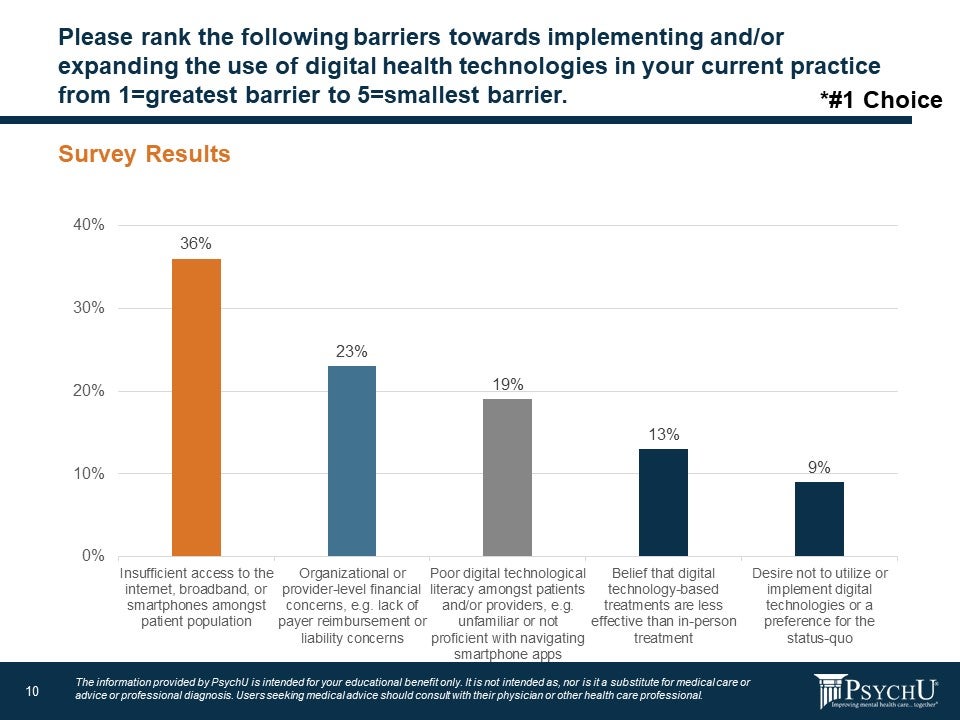

Survey respondents are also concerned about barriers that keep some patients from receiving the behavioral health care. Nearly 60% of respondents said their top concern regarding digital technology implementation was insufficient access to the internet, broadband, or smartphones among the patient population (36%) and concern that digital solutions will be reimbursed (23%).

Figure10: Barriers to Digital Technology

Forum participants agreed that overall, the shift to teletherapy by video or phone has worked well for most behavioral health patients during the pandemic. One provider reported that 65% of patients digitally opened patient education materials while in person patients were more likely to just throw out a paper-based educational hand-out. Providers also noted that patients who would be reluctant to attend a 12-step meeting in person, were more inclined to partake through videochat. Providers also said telehealth allowed them to make changes to treatment regimens more quickly and easily because it could be faster to consult with a patient to solve a problem over phone or videochat.

Suggestions from Forum participants specifically regarding digital solutions include:

- Telemedicine has worked very well for behavioral health during the pandemic allowing more people to seek behavioral health care due relaxed rules from CMS allowing providers and patients to participate in care from home. Data demonstrating these successes must be published and efforts must be made to ensure telehealth remains a viable option post-pandemic.

- Consider some types of “gamification” or behavioral economics-based strategies for telehealth where appropriate, to enhance consistent engagement.

- Consider the utility of “passive” data collection through use of wearables and smartphone applications where appropriate. For example, some smartwatches can somewhat effectively track sleep issues. This can lead to appropriate treatments without the patient having to spend the night in the office doing a sleep study. Other smartphone applications can help with suicidal ideation monitoring and helping patients develop their own safety plans.

- “Digital therapeutics” show great promise to reduce barriers to care, but they often lack a sufficient evidence-base to be considered as treatment and will need to be reimbursed by payers to encourage providers to recommend, prescribe or implement them within their practice.

Expert Consensus Topic 7: Discussion on Educational Resources

PsychU continues to evolve as an educational tool for behavioral health providers. To continue being effective, one important question for survey respondents was to find out what types of educational resources members would prefer to have. The main themes are:

- Case studies.

- Panel discussions.

- Specific educational interests.

Case Studies

Survey respondents would like to see more case studies and examples of success on PsychU to be able to improve their own practices. Phrases used include:

- “First make the care continuum make sense.”

- “Best practices, effective models of care.”

- “What are other countries doing well?”

- “Successful models; case studies.”

- “Presentations of solution-oriented examples.”

- “Sharing collaborative models or processes that have been successful in places around the country.”

- “Presenting innovative ways practitioners are overcoming barriers.”

Panel Discussions

Respondents would like to see more panel discussions between providers as well as ways to connect with peers. Topics survey respondents would like to see on PsychU include:

- “Find providers that are effectively and currently providing integrative services and utilize them.”

- “Increased ways to be PCPs on board.”

- “Improving education resources in public behavioral health services.”

- “Working with insurance companies; resources in specific states for continuum of care.”

- “Workshops—virtual or in person.”

Specific Educational Interests

These are several special topics survey respondents would like included on PsychU in the future:

- “Integrating medication assisted therapy (MAT).”

- “Education regarding primary care concerns which can impact behavioral health care.”

- “Articles to share with decision-makes on the importance of issues.”

- “Computer literacy for clients.”

- “It would be nice if you could offer more telehealth training or resources.”

Conclusions

The National Forum was conducted to garner expert consensus regarding solutions to expand effective behavioral treatment and fill in treatment gaps that preclude a seamless continuum of care. The outline and agenda for the meeting followed the survey which had been administered to 220 healthcare providers. Key takeaways from the forum included the need to integrate behavioral health more primary health care; improve coordination of systems, programs, payors, and providers; continue the expansion of telehealth and digital solutions accelerated by the limitations on face-to-face services due to the COVID-19 pandemic; and the need to increase opportunities for reimbursement for behavioral health services that encourages novel models of care, effective coordination of care between providers, and greater leveraging of telehealth resources. While the global COVID-19 pandemic has magnified the need for greater behavioral health resources, it has also afforded a glimpse into how we could improve the mobilization and delivery of these resource. Capitalizing on this insight now will require consolidating pandemic-related shifts in reimbursement that expanded resources for many and ongoing advocacy from stakeholders, including patients, providers, and payors, until the outstanding need for behavioral health resources is met.

Disclaimer

The information provided through PsychU is intended for the educational benefit of behavioral healthcare professionals and others who support behavioral health care. It is not intended as, nor is it a substitute for, medical care, advice, or professional diagnosis. Health care professionals should use their independent medical judgement when reviewing PsychU’s educational resources. Users seeking medical advice should consult with a health care professional. The content displayed in this report was developed by professionals at OPEN MINDS in conjunction with Otsuka employees. The expressed opinions, informational content, and links displayed do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of PsychU, PsychU Community members or Lundbeck, LLC, and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. All product and company names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective holders. Use of them does not imply any affiliation with or endorsement by them.

Footnotes

a The National Council 2018. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/press-releases/new-study-reveals-lack-of-access-as-root-cause-for-mental-health-crisis-in-america/

b PsychU National Forum Expert Panel, conducted October 13, 2020, and October 14, 2020, as described by participant Matt Torrington, M.D., Distinguished fellow of the American Society of Addiction Medicine with private practice in Culver City, California.

References

- The Lancet Global Health. (2020). Behavioral health matters. The Lancet Global Health, 8(11), E1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30432-0

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, January 1). Mental Illness. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml.

- Altraifi, A. and Rapfogel N. (2020, September 10). Behavioral health Care Was Severely Inequitable, Then Came the Coronavirus Crisis. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/disability/reports/2020/09/10/490221/mental-health-care-severely-inequitable-came-coronavirus-crisis/.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021, January 1). Mental Illness National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml.

- What You Should Be Thinking About Now. PsychU. (2021, June 7). https://www.psychu.org/what-you-should-be-thinking-about-now/.

- athenahealth Creates Online Telehealth Insights Dashboard to Help Practices Benchmark Their Performance and Find Opportunities to Better Meet Provider and Patient Needs. Business Wire. (2021, March 9). https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210309005235/en/athenahealth-Creates-Online-Telehealth-Insights-Dashboard-to-Help-Practices-Benchmark-Their-Performance-and-Find-Opportunities-to-Better-Meet-Provider-and-Patient-Needs.

- The Next Normal Health & Human Service Landscape. PsychU. (2020, December 29). https://www.psychu.org/the-next-normal-health-human-service-landscape-what-can-we-expect/.

- 4.5 Million More Behavioral Health Professionals Needed In U.S., A Shortage Of 87%. PsychU. (2021, May 27). https://psychu.org/4-5-million-more-behavioral-health-professionals-needed-in-u-s-a-shortage-of-87.

- Merritt Hawkins (2018). The Silent Shortage A White Paper Examining Supply, Demand and Recruitment Trends in Psychiatry. White Paper Series.

- New American Economy. (2017, October). The Silent Shortage: How Immigration Can Help Address the Large and Growing Psychiatrist Shortage in the United States. Http://Www.newamericaneconomy.org/Wp-Content/Uploads/2017/10/NAE_PsychiatristShortage_V6-1.Pdf. New American Economy. http://www.newamericaneconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/NAE_PsychiatristShortage_V6-1.pdf.

- Bishop, T. F., Press, M. J., Keyhani, S., & Pincus, H. A. (2014). Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(2), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862

- Moreno, C., Wykes, T., Galderisi, S., Nordentoft, M., Crossley, N., Jones, N., Cannon, M., Correll, C. U., Byrne, L., Carr, S., Chen, E., Gorwood, P., Johnson, S., Kärkkäinen, H., Krystal, J. H., Lee, J., Lieberman, J., López-Jaramillo, C., Männikkö, M., Phillips, M. R., … Arango, C. (2020). How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(9), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30307-2.

- Rodriguez, A. (2021, March 22). The pandemic ushered in ‘a new era of medicine’: These telehealth trends are likely here to stay. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2021/03/21/telehealth-trends-covid-19-mental-health-primary-care-coronavirus/4699979001/.

- Ohio Medicaid Makes COVID-19 Telehealth Rules Permanent. OPEN MINDS. (2021, April 13). https://openminds.com/market-intelligence/news/one-year-after-expansion-ohio-medicaid-provider-organizations-their-consumers-continue-to-embrace-telehealth/.

- The Next Normal Health & Human Service Landscape – What Can We Expect? OPEN MINDS. (2020, December 4). https://openminds.com/market-intelligence/executive-briefings/the-next-normal-health-human-service-landscape-what-can-we-expect/.

- February 2021 First Drop In Telehealth Utilization Since September 2020; Behavioral health Accounts For Over Half Of Sessions. OPEN MINDS. (2021, June 4). https://openminds.com/market-intelligence/news/commercially-insured-telehealth-utilization-fell-16-nationally-from-january-to-february-2021/.

- Herman, P. M., Dodds, S. E., Logue, M. D., Abraham, I., Rehfeld, R. A., Grizzle, A. J., Urbine, T. F., Horwitz, R., Crocker, R. L., & Maizes, V. H. (2014). IMPACT–Integrative Medicine PrimAry Care Trial: protocol for a comparative effectiveness study of the clinical and cost outcomes of an integrative primary care clinic model. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 14, 132. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-132

- IntegratedCareOnline.com. (2021, February). Results of a 2020 National Survey of Behavioral Health and Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities Provider Organizations with Case Studies. IntegratedCareOnline.com. https://s30502.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Intentional-Approaches-to-Integrated-Care-White-Paper-FINAL.pdf.

- AIMS Center at the University of Washington. (n.d.). Retrieved August 25, 2021, from https://aims.uw.edu/.

- The Behavioral health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). CMS. (n.d.). https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet.

- Post-COVID-19 Pandemic: Behavioral Health Providers Declare Telemedicine Is Here To Stay. PsychU. (2021, May 28). https://psychu.org/post-covid-19-pandemic-behavioral-health-providers-declare-telemedicine-is-here-to-stay/.

- Taskforce on Telehealth Policy Findings and Recommendations – Telehealth Effect on Total Cost of Care. NCQA. (2020, September 15). https://www.ncqa.org/programs/data-and-information-technology/telehealth/taskforce-on-telehealth-policy/taskforce-on-telehealth-policy-findings-and-recommendations-telehealth-effect-on-total-cost-of-care/.

- Emper, C. (2021, March 17). Congress Considers the Future of Telehealth. NextGen Healthcare. https://www.nextgen.com/blog/2021/march/nextgen-advisors-blog-congress-considers-future-of-telehealth.

Disclaimer: PsychU is supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. (OPDC), Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. (OAPI), and Lundbeck, LLC – committed supporters of the mental health treatment community. The opinions expressed by PsychU’s contributors are their own and are not endorsed or recommended by PsychU or its sponsors. The information provided through PsychU is intended for the educational benefit of mental health care professionals and others who support mental health care. It is not intended as, nor is it a substitute for, medical care, advice, or professional diagnosis. Health care professionals should use their independent medical judgement when reviewing PsychU’s educational resources. Users seeking medical advice should consult with a health care professional. No CME or CEU credits are available through any of the resources provided by PsychU. Some of the contributors may be paid consultants for OPDC, OAPI, and / or Lundbeck, LLC.